Late nineteenth century print of an outspan expedition in the Traansvaal. (Hullmandel & Walton’s Patent Lithotint)

outspan

South African

n[ˈaʊtˌspæn]

In this post I analyse Boycott Outspan Action’s Inspan Girls. In the process, I tell a fascinating story of colonial exploration, citrus capitalism and marketing that was subjected to deconstruction and parody by the BOA. Where outspanning was a specific type of white colonization, the BOA made inspanning into a moment of postcolonial critique, a moment where 1970s Outspan citrus was unveiled to stand for a more systematic and complete form of white colonization than the original British and Afrikaaner outspan trekkers would have ever thought possible.

The Outspan story starts with the mythologies created by communities of gold prospectors, journalists and explorers at the time of Boer and British expansion inland from Cape Town. To uitspan or outspan meant to unyoke cattle on new pastures. However, the process of uitspanning / outspanning became synonymous with much more than the literal unharnessing of cattle. It recalled the romance and danger associated with the vast Bushveld night, and it described a particular form of frontier colonialism based around the rush for gold, the mobility of wagons and the food stability afforded by cattle. To these temporary white communities ‘the outspan’ was a vast unchartered space of material and emotional potentiality, a space to expand into and across. The romance, capitalist speculation and hyper-masculinity of this frontier politics (taking place in Machonoland – meaning a land of/for men) is vibrantly evoked in James Percy Fitzpatrick’s short book, The Outspan:

It was in ’91, the year after the pioneers had cut their way through the Bush, with Selous to guide them, and occupied Machonaland. We followed their trail and lived again their anxious nights and days, when they, a small handful in a dense bush, at the mercy of the Matabele thousands, didn’t know at what hour they would be pounced on and massacred. We crossed the Lundi, and somewhere beyond where one of their worst nights was passed we outspanned in peace and security, and gossiped over the ruins of ancient temples and the graves of recent pioneers. There were half dozen of us, and we lay round the fire in lazy silence, too content to speak, simply living and drinking in indescribable glories of an ideal African night (1897: 6).

The son of two Irish immigrants, Fitzpatrick wrote several books based on his experiences as young transport rider based in the lowlands of the Traansvaal. He was encouraged by his friend Rudyard Kipling to write a collection of children’s stories based on the adventures he shared with his pet Staffordshire Bull Terrier. The resulting publication, Jock of the Bushveld (1907), sold exceptionally well to a British public demanding exciting imperial adventures that extolled ‘British’ virtues of loyalty and backing the underdog (Jock was the runt of the litter). The book went through four editions in 1907 and has been reprinted over a hundred times since. Current reproductions have largely removed the racist terminology of the original imperial text. For better or worse, the release of the animated film of the book also seems to have purged the title of much of its original narrative and context. However, its release is testament to Fitzpatrick’s enduring legacy.

Jock of the Bushveld (animated film, 2012)

From outpanning to Outspan Citrus

After the final Boer war Fitzpatrick entered politics and assumed the role of chief negotiator for Anglo-Afrikaaner relations. Putting his fame to profitable use, he became a capitalist with an obsessive desire to provide irrigation for the mass production of citrus for export. Fitzpatrick visited the Sunkist orange plantations in California and on return implemented new techniques for increasing citrus yields and productivity. Fitzpatrick created the outspan brand in 1922 as the label for citrus grown on his farms in the Sundays River Valley.

Fitzpatrick’s Outspan Citrus label. At this point Outspan was one of dozens of South African citrus labels that adorned oranges exported to Europe.

Established as the trading name for all South African export citrus in 1937, the Outspan identity was forged by a conglomerate of growers as a means to compete on an international scale with Sunkist (Cartright, 1977; Mather & Rowcroft, 2004). The name Outspan was chosen by the citrus exchange board as it was imbued with nationalistic nostalgia, came easily to the tongue, and was considered to honour Fitzpatrick after his death (Cartwright, 1977).

As the sole international system of provision and distribution for South African citrus for over fifty years, Outspan had high levels of visibility to consumers in the UK, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Benelux countries and Scandinavia, largely due to its sizeable budget for overseas marketing campaigns which by 1972 totalled over two million Rand (Mather & Rowcroft, 2004). Following the Sharpeville massacre of 1960, the company abstained from making explicit links between South Africa and its fruit in advertisements and marketing campaigns. Instead of creating geographical knowledges that idealized cultures of production, Outspan focused on brand building and fostering circuits of knowledges based on an individualized body politics of citrus consumption (Probyn, 2000). These knowledges suggested that health, vitality and beauty could be attained through the consumption of Outspan citrus (Mather & Rowcroft,2004; Mather & Mackenzie, 2006). Outspan knowledges were not simply represented, they elucidated particular embodied relationships between citrus fruit and consumers. These embodied relationships were carefully constructed in national advertisements and regional and local campaigns. Adverts in the UK and Holland during the 1970s suggested that increased citrus consumption could result in reduced hair-loss, and the bronzed, tanned bodies of Outspan endorsed bodies contrasted to the palor of the European consumer. The company recruited dozens of young white South African women to tour Europe as ‘Outspan Girls’ (Carter, 1977; Mather & Mackenzie, 2006; du Plessis, 1974; 2009; interview 2011); they engaged the public in ‘slimming galas’ and promoted ‘Outspan diets’ whilst deflecting all questions from apartheid onto the healthy properties of citrus (du Plessis 1974).

Through the Outspan Girls, the fruit company promoted their citrus in the embodiment of a white heteronormative femininity, where the value for the brand focused on the perceived attractiveness and youth of the female body, rather than on their ability to produce value enhancing knowledge. Mather & Rowcroft’s (2004) interviews with former girls demonstrate that they were trained in the offices of Outspan’s parent company – the Citrus Exchange – to deflect all questions on apartheid with smiles. Adverts for ‘Outspan Girls’ in South Africa demanded that applicants needed to be attractive enough to wear short skirts and lively and gay (Mather & Rowcroft, 2004: 407). In the Netherlands the BOA leader, Esau Du Plessis introduced the Dutch consumer to the ‘Outspan Girls’ in the opening to Bouwstenen Voor Apartheid:

Currently there are eight white South African girls travelling in the Netherlands, dressed in orange mini-dresses, wearing orange wigs on their heads and driving two remarkably large orange cars…Their role is to promote the consumption of the South African Outspan oranges. Outspan girls visit the shops and street markets, where they surprise buyers of Outspan fruit with gifts such as balloons, hats, display boards and citrus presses. About 10,000 Dutch stores may request a visit from these girls. A competition is arranged between the retailers to encourage at least a month long display of Outspan propaganda material in the shop (Translated from Dutch in Building Bricks for Apartheid, 1972: 6).

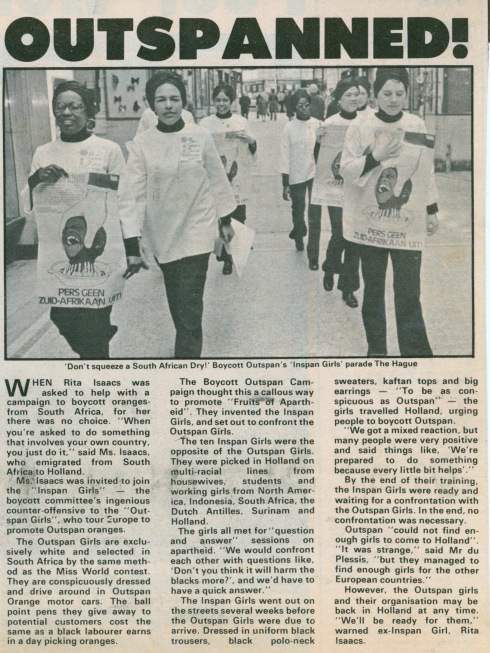

In order to counter the Outspan girls the BOA decided to form a multi-ethnic group of female activists who would attempt to hijack the promotional campaigns of the touring Outspan Girls. The main point of the Inspan Girls was that they embodied femininity from multiple ethnicities. They were not black in the way Mather & Mackenzie (2006) point out; the twelve girls came from a variety of ethnicities (Tan, interview 2011; du Plessis, 1974; 2011).

The multi-ethnic Inspan Girls, 1973. Lioe Tan and Rita Isaacs Jonathan bottom left and bottom right receptively. Marguerite Isaacs middle right.

The stark black and white binary (of Inspan Girls/Outpsan Girls) is inaccurate and is misrepresentative of the BOA’s specific intention, and its broader ideology. The Outpan girls presented an essentialised version of race in embodying South Africa. Through their ethnic multiplicities the ‘Inspan Girls’ were an embodied attempt to deconstruct the simple binary.

Article reflecting on impact of the Inspan Girls in the global activist publication, the New Internationalist, 1976. Contains short interview extracts with Rita Isaacs-Jonathan and Esau du Plessis

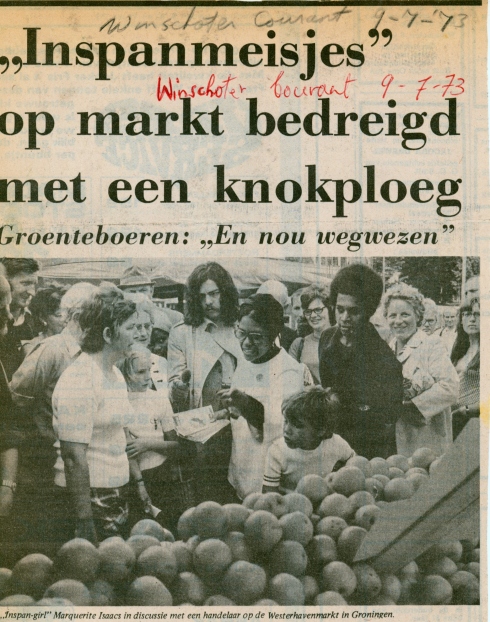

The Inspan Girls, or ‘Inspanmeisje’, as they were known by the Dutch press became minor celebrities in the Netherlands for several months in 1972-73. Photographs of the Inspan Girls at work outside Dutch supermarkets and markets accompanied newspaper articles on apartheid in the regional and national press. Several of the activists were interviewed by reporters and radio broadcasters, and asked for their opinions on a range of subjects. During these interviews, boycotters such as Faith de Haas took the opportunity to speak directly to female consumers, to ask ‘housewives’ if they knew what buying Outspan implied:

Article interviewing Inspan Girl, Faith de Haas, in the Oost Groninger Dagblad (East Groningen News), Wednesday July 11, 1973. The headline states “Inspan Girl Faith De Haas knows what she is talking about when it comes to Apartheid”. De Haas suggests that due to her Inspan commitments, “my husband and I couldn’t see each other”. the article continues with: “Ms, do you know where those oranges come from? This is the question Ms Faith from Groningen has asked hundreds of times to housewives who innocently bought Outspan oranges”.

During an interview in 2010, former ‘Inspan Girl’ Lioe Tan explained to me that persuasion and an ability to engage in political dialogue were crucial aspects of the Inspanmeisjes’ work:

Lioe: We gave out information on South Africa, and the apartheid system, and the orange farms, and we told the public that the farm workers earned 75 cents per month. We handed leaflets to people outside supermarkets, and started discussions with shoppers. And one time a store manager was furious with us and sprayed us with a fire extinguisher!

Hugh: Were people receptive to what you were doing?

Lioe: Some were, and some were not of course because of the blood ties. And we had conversations where we would persuade people of the worth of the boycott. Some people didn’t think the boycott would help the workers, but we told them that they already had such a low wage, and the ANC and SACTU asked for the boycott. We told Dutch shoppers that the boycott was their idea, not ours.

Hugh: How do you think the femininity of the Inspan Girls differed from that of the Outspan Girls?

Lioe: We were activists! They were paid! Most of the Inspan Girls were politically active in many spheres, and did other things for the BOA like translating texts from English into Dutch. Rita Isaacs was a spokeswoman for the BOA, and she spoke at the congress in 1973.

Inspan Girl Marguerite Isaacs in discussion with greengrocer traders in a Groningen market. Winschoter Courant, July 9th, 1973.

The Inspan Girls had a degree of autonomy producing knowledge about apartheid and the boycott. They were required to perform a politics of relativity, where the personal, the local and the global were interconnected through chains of suggested causation.

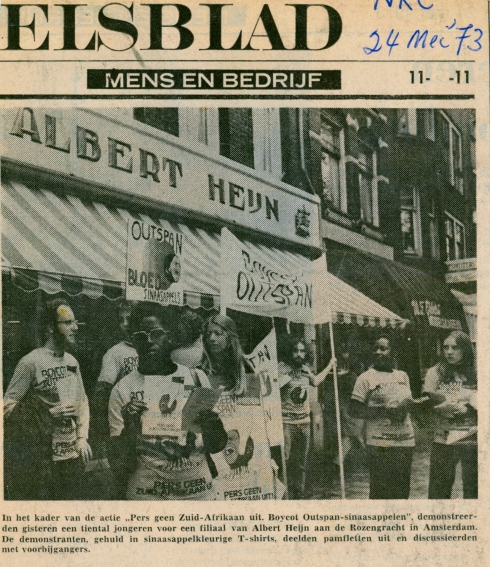

The Inspan Girls with other BOA activists outside the Dutch supermarket chain, Albert Heijn in Amsterdam. NRC, 24th May, 1973. Albert Heijn buckled under the pressure from the BOA and halted imports of Outspan after just a few days of pickets and demonstrations outside their stores.

Debating the merits of boycotting citrus made different demands to the emotional labour (Hochschild, 1984) requirements placed on the Outspan Girls who would have to appear happy, cheerful and healthy at all times, whilst disguising the ontological construction of racial identities. Mather & Mackenzie argue that the Outspan Girls embodied an essentialised interpretation of race. I contest that their identity was more complicated than this; race and gender were entwined in the embodied public display of an objective colonial patriarchy; a Cartesian façade which subordinated their bodies as metaphorical instruments (Grosz, 1994), and demanded public emotional labour, heteronormative sexual performance, and an uncritical consuming public, to obscure and distract from apartheid conditions of citrus production.

Subsequent to the unveiling of the Inspan Girls at the BOA press conference in September 1972, and the threat of a confrontation in June 1973, the Outspan Girls never returned to Holland, and their tours of other European countries became fraught with controversy. The former leader of the Dutch Third World Shops (of which there were roughly two hundred), Hans Beerends told me during an interview in 2011 that by 1975 the “BOA had won, they had won and had nothing left to do”. This is an interesting reading of the BOA, the organization still had plenty to do (the BOA would operate for another seventeen years, in which time they would form the French anti -apartheid movement, conduct anti-emigration campaigns, arrange congresses, and embark on ten years of anti-racism tours and campaigns), but the premise of Beerends’ assertion was that the Inspan Girls achieved what their name demanded. They managed to reign in, and harness the expansive citrus capitalism as embodied and advertized by the Outspan Girls.

The Inspan Girls were so effective because their marked display of multi-racial ontology and reflexivity over the importance of race in marketing was achieved in a direct relationship with Outspan oranges. They asked uncomfortable questions about the ontological formation of Outspan Girls, the production of citrus, and racial construction of South Africa itself. They produced what we might describe today as situated and messy knowledges; they engaged in relational debate, drew from personal experiences of apartheid and racism, and they complicated neat divisions of power. In comparison, the Outspan Girls reproduced the positivist philosophies of apartheid. Their bodies conspicuously displayed white patriarchy, and their remit was to use them to replace the production of relational knowledge and to distract from the troubling dissonance between the Netherlands and the repression of black South Africa.

So for the BOA, to inspan meant for white south Africa to beat a retreat. It meant to burn the tentacles of apartheid citrus capitalism so acutely that they would never return to seek nourishment from the Netherlands. The Inspan Girls were the moment of no return for Outspan. By 1974, the BOA had become a virus that had hijacked the Outspan brand, distribution chain, and contexts of consumption. In less than a year the BOA had mutated the U.S.P of the brand from a healthy, fun and sun-drenched alternative to Sunkist, to an avatar for apartheid. Once the Inspan Girls had signalled their intent, the longer the brand remained visible and in public consciousness, the more it stood for the unpalatable truths of apartheid subjugation.

I believe the Inspan Girls should be memorialised as a micro postcolonial movement; to inspan was to decolonize. To strip back and shame the apartheid regime into an economic and symbolic retreat. And to offer a multi-ethnic and alternative form of knowledge production to apartheid political economies. As a measure of their success, by 1973-4 the BOA had attracted attention from Eschel Rhoodie’s incredulously named ‘South African Ministry of Propaganda’. Du Plessis became the subject of a smear campaign by Rhoodie who falsely accused the BOA leader of taking money in exchange for activist contact details. The BOA’s squeezing image was banned, and the South African embassy in Amsterdam pleaded with the Dutch government cut its small ‘third world development fund’ subsidy to the BOA (Bosgra 2009; du Plessis, 2012).

Recommended reading

Achterhuis H, Grundy K, Hultman T, Kramer R, Morton D, du Plessis E (1975) Apartheid in Exportverpakking. Rotterdam: BOA

Cartwright A (1977) Outspan Golden Harvest. A History of the South African Citrus Industry.Pretoria: The Citrus Exchange

du Plessis, E (1972) Outspan: Bouwstenen voor Apartheid. Rotterdam: BOA

Fitzpatrick, P (1897) The Outspan; tales of South Africa. Cape Town: W. Heinemann

Legassick, (1995 [1972]) “British Hegemony and the origins of segregation in South Africa, 1901-14”, In Dubow and Beinart (eds) Segregation and Apartheid in Twentieth Century South Africa. Routledge: London

Lupton, D (1997) Food, the Body and the Self. London: Sage

Mather C, Rowcroft C (2004) “Citrus, Apartheid, and the struggle to (re)present Outspan oranges” in Reimer & Hughes (eds.), Geographies of Commodity Chains. Routledge: London, pp 156-171

Mather C, Mackenzie C (2006) The body in transnational commodity cultures: South Africa’s outspan ‘girl’s’ campaign. Social and Cultural Geography, 7: 3, 403-20

Probyn, E (2000) Carnal Appetites FoodSexIdentities. London & New York: Routledge

Roskam, K (1960) Apartheid and Discrimination. Leiden: Leiden University Press

One Response to “From Outspanning to Inspanning: Outspan Citrus and the Remarkable Inspan Girls”